Biography

Susanna Helke, born 1967 in Tampere (Finland). Studied journalism and communication studies at the University of Tampere. Studied photography and new media at the University of Art and Design, Helsinki, and San Francisco State University. Her doctoral thesis was entitled „The Legacy of Nanook - the documentary meets the fictional in style and approach“. From 1991 to 1994 Susanna Helke took part in several group exhibitions as a photographer. She produced documentary radio programmes, shot short films for Finnish television, and worked as a freelance photographer for various magazines. She lives and works as a filmmaker and lecturer in Helsinki and is a member of the European Film Academy.

Virpi Suutari, born 1967 in Rovaniemi (Finland). Studied journalism and communication studies at the University of Tampere and graduated in photography from the University of Art and Design in Helsinki in 1996. Since 1989 she has worked as a journalist for several newspapers and magazines, including the Sunday and monthly supplements for the largest Finnish newspaper „Helsingin Sanomat“ and the cultural newspaper „Image“. She has done several short films for Finnish television and photo exhibitions. Virpi Suutari lives and works as a filmmaker and journalist in Helsinki, is married and has three children. She is a member of the European Film Academy.

Filmography Susanna Helke and Virpi Suutari

PITKIN TIETÄ PIENI LAPSI (Along the Road Little Child, 2005); JOUTILAAT (The Idle Ones, 2001), Documentary about unemployed young men in northern Finland; SAIPPUAKAUPPIAAN SUNNUNTAI (Soapdealer‘s Sunday, 1998), A documentary about getting lost in time; VALKOINEN TAIVAS (White Sky, 1998) A documentary about coping with destruction; SYNTI DOKUMENTTI JOKAPÄIVÄISISTÄ RIKOKSISTA (Sin - A Documentary of Daily Offences, 1996) A documentary based on the seven deadly sins; JOSKUS JOPA HÄVYTÖN (Insolence, 1994) A documentary about everyday female aggression; ELÄIMEN KÄSI (Animal‘s hand, 1994) A video essay about relationships in nature, the natural and the unnatural. A playful approach to nature clichés; RAKASTAJA (Lover, 1994) A documentary about love between two old people

Essay

Nature Mort, and the cities are perishing too

by Olaf Möller

It is not often the case that a pair of directors are not connected either intimately or through family ties, in other words, that two unrelated people join forces to develop, to create films together. The Finnish documentary filmmakers Susanna Helke and Virpi Suutari are among these rare cases: they are neither sisters nor a couple, they are not necessarily even to be found on the same continent, yet they have been fourhandedly realising documentary films since the early nineties, always taking responsibility for script and direction together (and sometimes editing as well); nor is there any division of labor or individual specialisation recognisable in the other credits. What they have in common is, to begin with, only the year of their birth (1967) and their higher education careers: both studied art and design in Helsinki and journalism and communication studies in Lahti.

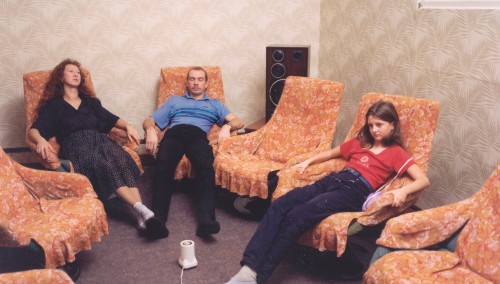

Helke and Suutari achieved their international breakthrough (they had long been well known already in the relevant circles) with one of their most untypically produced works, THE IDLE ONES (JOUTILAAT, 2001), a feature- length observation of three older adolescents in a small town in the north of Finland. None of the three really has much of an idea of the whys and wherefores of their lives: none of them seem to have any special talents, there is little evidence of any special interests. What all of them are facing is an existence in quiet functionality and relative social security, which will one day simply come to an end – in light of these kinds of perspectives, it is not hard to understand why none of them are particularly interested in growing up, just letting the days drift past and hoping that the rest of their lives will not start tomorrow. What is illustrated here is the characteristic Finnish attitude to life, how normality appears within certain aesthetic parameters: distanced, two-dimensional, concretely joined. It is a mirror revealing why Finland has such a high suicide and murder rate: that much control contains what is primitively seething, the needs requiring egotism to satisfy them, which Finnish society denies.

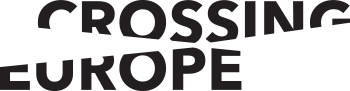

It is all brought to a point, and considerably more ironically when viewed with a suitable disposition, in SAIPPUAKAUPPIAAN SUNNUNTAI (SOAPDEALER‘S SUNDAY, 1998): scenes from the life of a family without a regular income. The father Kari is unemployed and trying his luck as a soap and vitamins peddler, but since he does not look particularly interesting and is not very convincing in the way he presents his secular sermons, his appearances have a rather depressing effect. Meanwhile, the mother Pirjo is expecting her fourth child. Their flat is bright and manageable – every picture is clearly constructed, set – and somewhat resembles an aquarium. This is the way the welfare state hell has always been imagined, and yet living in it has often seemed so desirable. SOAPDEALER‘S SUNDAY is a kind of social still life: time trickles away.

Helke and Suutari often film the residence and its inhabitants so that this trickling is present in the distances. In the faces of the parents there is worry and toil and a will to keep hoping – in the gestures of the children a different life, at least the possibility of it, yet the parents‘ existence looms ominously with its discount coupon values and even has a certain melancholy attraction about it.

Children as a distorting mirror of the „larger world“ are also at the heart of the latest film by Helke and Suutari: ALONG THE ROAD LITTLE CHILD (PITKIN TIETÄ PIENI LAPSI, 2005). Unlike in THE IDLE ONES, here the starting situation holds both possibilities and conflicts: the cooperation between Finnish and Somali children building a house together in the little woods next to a housing estate (one could see a nice image for the work by the two filmmakers in this). Much is absorbed by this playing/working together here, even the quirky teasing with religious references (the film is advertised with the lovely quotation, „Here you can eat pork. It is so dark that Allah does not see anything.“). There is nothing utopian about this, it is simply rational, which is sometimes more meaningful. There is something whimsical, gracefully agile about ALONG THE ROAD LITTLE CHILD, and in a sense it is the most fragmented work by the two filmmakers so far: an erratic pleasure in being surprised – again and again, the camera is cheerfully hard-pressed to keep up with the children, shaking the way the children skip, colliding with austerely poetic stylisations, images of grasses and ferns, sky, clouds, allegorically compact voice-over narrations evoking meta-levels. A core image, so to speak, is that of the dark-skinned children in front of white birch trees: everything is really all there in this image ... here and also in the insane greenish yellow that determines the film.

Whereas in ALONG THE ROAD LITTLE CHILD everything is just evolving, in WHITE SKY (VALKOINEN TAIVAS, 1998), it has already passed, is now in decay: an industrial site in northern Russia and the consequences of its contamination with heavy metals and dioxide, the devastation of the world and the people – dead nature, empty houses. The memories that imbue the swarm of playing children with a certain gravity in ALONG THE ROAD LITTLE CHILD – but perhaps also show how much can be overcome, if not forgotten – have become a kind of perverse present in WHITE SKY. There is no image whose corroded emptiness does not tell of all that has been. It is not a matter of specific memories, as with the children, but rather of the realisation that there is nothing more that can be remembered here, that there is no room left for that, and all that is left is the waiting for some far distant time. Yet life goes on, paying no heed to disasters, if they do not destroy it. Life is unruly and obstinate, staging itself counter to the measures of society. It keeps on going.

If THE IDLE ONES is one extreme point in Helke and Suutari‘s work, then the relatively early SIN – A DOCUMENTARY ON DAILY OFFENCES (SYNTI – DOKUMENTTI JOKAPÄIVÄISISTÄ RIKOKSISTA, 1996) is another. It is a kind of experimental essay-opera without singing. The seven deadly sins structure the sometimes monumental tableaux vivants – sometimes in peepholes, sometimes in broad pans – full of people, who sometimes say something and sometimes are simply there staring. Private and professional anecdotes collide here with allegorically set text panels and on-screen with off-screen sounds. And over all of this there is a tremendously resounding music – something that is obviously important to Helke and Suutari: almost all of their films have elaborate soundtracks that repeatedly underscore the moment of fiction/condensation/the dramatisation of existence.

Like most auteurs from the Finnish production company Kinotar – led by Mika Taanila and Kanerva Cederström – Helke and Suutari are also only marginally interested in the dogma of documentary directness, in its drama that ultimately tends to merely affirm conditions rather than question them: this creates facts, but not visions. What excites and inspires Helke and Suutari is creating realities from actuality, working at the fracture between what is and what could be.