Biography

Šarūnas Bartas, (international spelling also: Sharunas Bartas), born 1964 in Šiauliai, Lithuania, studied at the Moscow Film Academy VGIK and then founded the first independent production company in Lithuania, KINEM A. Bartas‘ directing work was met with interest not only at festivals, but also in commercial French cinemas. Leos Carax, Valeria Bruni-Tedeschi and the French-Portuguese producer Paolo Branco have worked with him.

Tofolarija (1985, 16 min), Praėjusios Dienos Atminimui (In Memory of the Day Passed By, 1990, 40 min), Trys Dienos (Drei Tage / Three Days / 1991, 75 min, auch Musik), Koridorius (Korridor / The Corridor, 1995, 85 min), Wir sind wenige (Few of Us, 1996, 105 min), A Casa (Das Haus / The House, 1997, 120 min), Pola X (1999, 134 min, Regie: Leos Carax - nur Darsteller), Freedom (2000, 96 min), Arseny Tarkovsky: Eternal Presence (2004, nur Produzent), Visions of Europe - Episode Children lose nothing (2004), Seven Invisible Men (2005, 119 min)

Arūnas Matelis, born 1961 in Kaunas/Lithuania, studied mathematics and then film directing in Vilnius. In 1992 he founded his own production company, NOM INUM, with which he has meanwhile produced about 20 films. He is a Member of the European Film Academy. Films directed and produced by Arūnas Matelis were presented and distiguished many film festivals around the world.

Pelesos milžinai (Giants of Pelesa, 1989, 10 min), Baltijos kelias (Baltic Way; mit Audrius Stonys, 1989, 10 min), Dešimt minučių prieš Ikaro skrydį (Ten Minutes Before Ikarus‘ Flight, 1991, 10 min), Autoportretas (Selfportrait / Selbstporträt, 1993, 10 min), Pirmasis atsisveikinimas su Rojum (The First Farewell to Paradise, 1998, 15 min), Iš dar nebaigtų Jeruzalės pasakų (From Unfinished Tales of Jerusalem, 1996, 26 min), Priverstinės emigracijos dienoraštis (1999, 22 min; Zweite Kamera: Audrius Stonys), Skrydis per Lietuvą arba 510 sekundžių tylos (Flight over Lithuania or 510 Seconds of Silence, mit Audrius Stonys, 2000, 8 min), Sekm andienis. Evangelija pagal liftininką Albertą (Sunday. The Gospel According to Liftman Albertas, 2003, 19 min), Prieš parskrendant I Žemę (Before Flying Back to the Earth / Vor dem Flug zur Erde, 2005, 56 min)

Audrius Stonys, born 1966 in Vilnius. Studied at the Vilnius Conservatory and then worked at Jonas Mekas’ Anthology Film Archive in New York. He taught documentary filmmaking from 2004-2005 in Copenhagen and in 2006 in Tokyo. Stonys is a Member of the European Film Academy and the European Documentary Network. He made 14 films as an independent filmmaker and producer.

Atverti duris ateinančiam (Open the Door to Him Who Comes, 1989, 10 min), Baltijos Kelias (Baltic Way, mit Arunas Matelis, 1990, 10 min), Neregių žemė (Earth of the Blind, 1992, 24 min), Griuvėsių apaštalas (Apostle of Ruins, 1993, 18 min), Antigravitacija (Antigravitation, 1995, 20 min), Skrajojimai mėlyname lauke (Flying over the Blue Field, 1996, 20 min; Produzent: Arunas Matelis), Uostas (Harbour, 1998, 10 min), Fedia, Trys minutės po Didžiojo sprogimo (Fedia, Three Minutes after the Big Bang, 1999, 10 min), Skrydis per Lietuvą arba 510 sekundžių tylos (510 Seconds of Silence; mit Arunas Matelis, 2000, 8 min), Viena (Alone, 2001, 16 min), Paskutinis Vagonas (The Last Car, 2002, 28 min), Countdown (2004, 45 min), Ūkų ūkai (Mist of Mists, 2006, 30 min), Varpas (The Bell / Die Glocke 2007, 56 min)

Essay

The Poetic Feature and Documentary Films by the New Generation of Lithuanian Filmmakers

Šarūnas Bartas, Arunas Matelis and Audrius Stonys.

“I live here, grew up here. I am where I am. I am as I am. For me, tradition is something that always remains the same.”1(Šarūnas Bartas)

“Tant qu'il y aura sur terre un chalet comme celui-là (Studio Kinema), dans une forêt, avec un garçon comme Sharunas pour y travailler et y inventer, je serai tout à fait optimiste quant au cinéma.2“ (Leo Carax)

Small countries3 are often caught in between larger powers. This is also the case with Lithuania, which throughout the centuries has repeatedly come under Polish, German and Russian/Soviet domination. In reaction to a national revolt that was crushed by the Czarist army in the late 19th century, the Lithuanians were forbidden to use their own language and writing. Everything was to be written in Cyrillic and thought in Russian. Resistance arose in Lithuania. National movements sprang up everywhere. Book smuggling proliferated. The Lithuanians preserved their own culture obstinately then and also later when the Germans and finally the Soviets came. Even today, Lithuanians are proud of having been the last pagan people in Europe. Until the end of the 14th century they resisted Christianization in their belief in the soul of nature. Under Soviet domination, on the other hand, the Lithuanians chose none other than the Catholic church as protection for their resistance.

In 1940 Stalin ordered the Red Army to invade Lithuania and, following a German intermezzo, the country that had declared its independence only twenty-two years before faced Sovietization. Many Lithuanians emigrated to the USA, such as the “godfather of the American avant-garde” Jonas Mekas4 or the parents of the New Yorker film poet Marie Menkevicius aka Marie Menken. 100,000 Lithuanians went into the forests and fought as partisans. Russian was also the official language in the Lithuanian Socialist Soviet Republic, Lithuanian was only officially declared the state language again in 1988.

This brief introduction may help to understand a certain obstinately introspective attitude, but most of all a fundamental scepticism about language, which is inherent to many films of the “poetic” Lithuanian school. When the filmmaker Šarūnas Bartas, born in 1964, calls “words parasites of images”5, the reason for this statement may be found in the past – over the centuries the use of language in Lithuania lost its innocence and could not be taken for granted. In this sense Bartas is a traditionalist – in the tradition of a permanently felt, inner resistance.

But let’s not skip ahead. During the Soviet era the state had a monopoly on film production. Since 1949 there has been a film studio in Vilnius, originally used only to produce weekly newsreels, expanded in 1956 and renamed Lietuvos Kinostudija6 – it is the only one in Lithuania. Documentary films that were produced here provided instructions for maximizing productivity (“Efficient Ploughing”) and for political consensus. It was only in the 1960s that an intrinsically Lithuanian school emerged. Films were made in the awareness of state censorship that were full of allusions, omissions and metaphors, which principally only a Lithuanian could understand. Despite all caution, some of these works were not released by the Soviet authorities, such as “Jausmai” / “Feelings” (1966) by Algirdas Dausa and Almantas Grikevicius or “Birzelis, vasaros pradzia” / “June, the Beginning of Summer” (1969) by Raomondas Vabalas.

The Lithuanian filmmakers of the sixties, Robertas Verba and his successors, purposely looked for the marginal figures that Soviet cinema left out: their films were devoted to the old people, the oddballs from the province, people who did not appear before the camera as examples, as worker-heroes, but more as gentle metaphors. And whereas the sun was expected to shine in the art of Social Realism, this Lithuanian cinema turned more to dark fatalism.

After Perestroika the generation of the sixties withdrew. With Vytautas Zalakevicius (“Adomas nori buti zmogumi” / “Adam wants to be a man”, 1959; “Vienos Dienos Kronika” / “Chronicles of One Day”, 1963; “Eto sladkoe slovo svoboda!” / “This sweet word – freedom!”, 1973) one of the great screenwriters and directors of Lithuania died in 1996. It was the end of an era.

Yet like it or not, the roots of today’s Lithuanian filmmaking reach into the Soviet era: Šarūnas Bartas, probably the most prominent representative of the new generation of Lithuanian filmmakers, still trained in Moscow. He studied directing at the Moscow State Film Academy (VGIK) – like the Lithuanian Zalakevicius, but also like the Russians Andrei Tarkovsky, Nikita Mikhalkov and Alexander Sokurov.[7] His colleagues Audrius Stonys (*1966) and Arunas Matelis (*1961) already studied film and television directing at the conservatory in Vilnius in the eighties. After 1989 Stonys also worked in Jonas Mekas’ Cinema Anthology Archive in New York.

In 1989 the “singing revolution”8 reached its climax in Lithuania: on 23 August of that year the eyes of the world were on Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania as an unbroken human chain (“Baltic Chain”) formed between their capital cities, of people singing, praying, holding candles in their hands. In collaboration with six camera people shooting in parallel along the chain, Audrius Stonys and Arunas Matelis documented this event in their short film – shown at Crossing Europe – “Baltijos Kelias” / “Baltic Way”.

The process of independence that took place in the country step by step from then on, also took place in the film landscape. With Studio Kinema Šarūnas Bartas founded the first independent production company in Lithuania as early as 1987.9 In 1992, immediately upon graduation, Arunas Matelis followed with Nominum.10

Even before founding this company11, Matelis made the short film “Desimt Minuciu Pries Ikaro Skrydi” / “10 Minutes before Icarus’ Flight”, which was distinguished in Oberhausen as best short film and acclaimed in Lithuania itself as a kind of director’s manifesto for what Matelis calls “poetic documentation”. Among others, the camera in “Desimt Minuciu” follows a Russian drinker in his flat as he sings an outline of Lithuanian history (!) within only a few moments: from the Yiddish folk song to a barked German parody of the partisan anthem. The man stumbles aimlessly through the picturesquely decayed alleys of the district of Uzupis – an image of Lithuania, kicked but still alive. “Desimt Minuciu” takes up the tradition of the metaphorical image of the preceding generation of directors. The metaphorical image and the heavily manipulated, expressive sound together indicate something beyond the concrete meaning.

Two years later, Matelis’ colleague and friend Audrius Stonys was awarded the Felix for Best European Documentary Film for “Neregiu Zeme” / “Land of the Blind” (a Studio Kinema production). “Neregiu Zeme” goes a step further in the direction of metaphorical abstraction: images of a grazing cow are contrasted in an expressive montage of associations with smokestacks rising steeply into the sky and shying horses. Unlike Eisenstein, the creator of this technique, here the rhythm of the cuts is peaceful. The long shots take their time for the inherent themes of the film – work, life and death. Stonys’ decision to use 35mm black and white material also seems to be programmatic. The austerity of these images may be no longer directed against the dominant Soviet culture, but against the dominant capitalist culture and its noisy colourfulness.

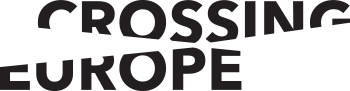

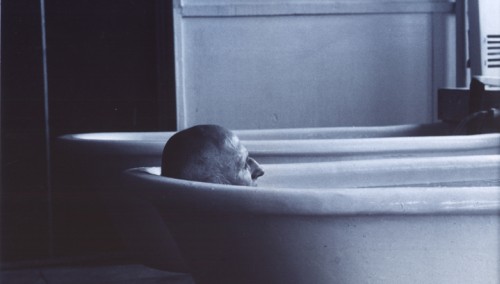

Films like these have a “purging effect on the eyes accustomed to dramatic gluttony, a purifying trip to the boundaries of nothingness.”12 And in fact Stonys shot a film in a sanatorium in 1998. His “Uoastas” / “Harbour”, also shot on 35mm black and white material, shows old people in steam and bath chambers: naked bodies – free from all attributes except those that time has added to them.

Both works by Šarūnas Bartas, also shown at Crossing Europe, are marked by the same winterly, late afternoon atmosphere. In “Praejusios Dienos Atminimuj” / “Memories of a Past Day” (1990) and “Trys Dienos” / “Three Days” (1991) the people seem to be waiting for something, an end, perhaps a beginning. Dissolving the boundary between documentation and fiction, which is alluded to in “Land of the Blind” and “Desimt Minuciu”, happens more clearly here: a bearded puppeteer shuffles in staged cuts through “Memories”, while in “Three Days”, hanging out in post-totalitarian space itself becomes the feature film plot.

This is something else that Bartas, Stonys and Matelis strongly have in common: their stories develop from the space.13 The grey walls, the curbs, the crooked steps are always there first. Then the bodies come into play and stumble into the situations. In the early films of the three it is the space – and not any social system – that defines the coordinates of life. The way Bartas, Stonys, Matelis photograph buildings, streets and public space is accordingly timeless. Lithuania is what Lithuania remains – like the opening quotation from Šarūnas Bartas. Ultimately, in “Pires Parskrendant i Zeme” / “Before Flying Back to the Earth” (2005), Arunas Matelis turns to a very specific building. “Pries Parskrendant” is about the children’s hospital in Vilnius, a film about corridors, halls and wards, about girls and boys with shaved heads and their parents, about fear and hope, and about death. Especially because it is never mentioned, death is constantly present: its image is found in a room full of rolled up mattresses that a staff member pushes into the disinfection ovens. Anyone who thinks Lithuanian fatalism reached its peak in this film would be wrong. “Pries Parskrendant i Zeme” is a lively, almost cheerful work.

At the latest with this film, which was awarded the main prize at the IDFA Amsterdam, the Documenta Madrid and the Documentary Film Festival Leipzig, Lithuanian filmmaking is assured of Europe’s attention.

1 Interview with Šarūnas Bartas, in: Litauische Bilderwelten / The World of Lithuanian Images, catalogue concept: Zivilé Pipinyté, Myriam Beger, Lolita Jablonskiené, Biruté Pankunaité, Ruta Pileckaité. Contemporary Art Information Centre of the Lithuanian Art Museum, 2002, p. 58

2 Program book Xenix-Kino/Zürich, Baltische Bilderwelten, Filmschau March 1999

3 With an area of 65,000 square kilometer, the largest of the three Baltic countries, Lithuania, is roughly a quarter smaller than Austria. The population (3.4 million) is distributed relatively thinly: in Austria there is an average of twice as many inhabitants per square kilometer (52/99). Source: Wikipedia.

4 In November 2007 the New Yorker filmmaker founded the Jonas Mekas Visual Arts Center / Vilnius.

5 December 2006 in the Filmkrant interview with Dana Linssen. (“It’s all over with humanity anyway”) See: www.filmkrant.nl/av/org/filmkran/archief/fk283/bartas.html

6 Cf. Clark, George: The will to survive. Lithuanian film surveyed at Karlovy Vary’s film festival. ww.kinoeye.org/04/04/clark04.php

7 Bartas consistently and expressly rejects the comparison with Sokurov and Tarkovsky that international critics frequently apply to him.

8 The singing of nationalist songs (e.g. the anthems of the Baltic states) was strictly forbidden in the Soviet Union: sanctions were threatened ranging from employment termination to being deported to Siberia. During Perestroika, 1988-1992, people sang at national assemblies and peaceful demonstrations (especially in Lithuania, Vingio Parkas, Kalnu Parkas). Hundreds of thousands of people collected in public places to express their opinions of Soviet occupation and annexation. People especially sang traditional folk songs that united the people ideally and emotionally, thus testifying to the shared cultural experience and past. (Source: Wikipedia)

9 Originally he only wanted to realize his diploma film with it – and thus entered into the history of the country more or less accidentally. In addition to Bartas’ own films, Studio Kinema meanwhile also (co-)produces works by Audrius Stonys, Valdas Navasaitis, Arturas Jevdokimovas and Tomas Donela.

10 According to their own description, the company focuses on “creative documentary films”. See: www.nominum.lt

11 The state Lietuvos Kino Studija is listed as producer in the opening credits.

12 Merten Wortmann in DIE ZEIT on Šarūnas Bartas’ “Freedom”. See www.zeit.de/2000/38/2000038_venedig_neu.xml

13 Later films by Šarūnas Bartas, which he has produced with the Portuguese arthouse producer Paolo Branco, have the location fixed in the title: “Koridorus” / “Corridor” (1995) and “A Casa” / “The House” (1997).