Biography

Helena Třeštíková, born in 1949, studied at the famous Prague film academy FAMU. Since 1974 the documentary film director has made around 50 documentary works of different lengths and in various formats. Her films deal with interpersonal relationships, follow biographies, and revolve around social and socio-political issues – always against the backdrop of Czech society in transformation. Later, she then turned to the filmic long-term observation of life stories and struggles. The family portrait from Private Universe, for example, covers a period of no less than 37 (!) years. Helena Třeštíková worked for many years for Czech television, for which she made the successful documentary series Marriage Stories in 1987. In this series, which was followed 20 years later by a second season, she portrayed six married couples during the period of 1987 to 2006. In 1991, together with colleagues from the film branch and sociologists, Helena Třeštíková founded the Film and Sociology Foundation. What followed were more long-term film studies. In 2007, for a brief period Třeštíková was part of the Czech government as Minister for Culture and Art. International fame and acclaim came finally with the award-winning portrait trilogy Marcela, René, and Katka. Since 2002, she teaches in the department of documentary film at the FAMU. Mall ory and Lída Baarová – Doomed Beauty are Třeštíková’s latest films. The screening in Linz will mark their Austrian Premiere.

Films at CROSSING EUROPE film festival Linz 2016

Lída Baarová – Zkáza krásou (Lída Baarová – Doomed Beauty, 2016, doc), Mallory (2015, doc), Vojta Lavička – Nahoru a dolů (Vojta Lavicka – Ups and Downs, 2013, doc; CE ’14), Jakub Špalek – Život s Kašp arem (Jakub Špalek – Life with Jester, 2013, doc), Soukromý vesmír (Private Universe, 2012, doc; CE ’13), Katka (2010, doc), René (2008, doc; CE ’09), Marcela (2006, doc), Řekni mi něco o sobě – Láďa (Tell Me Something About Yourself – Láďa, 1994, doc), Řekni mi něco o sobě – Pavl ína (Tell Me Something About Yourself – Pavlína, 1992, doc), Manželské etudy – Ivana a Václav (Marriage Stories – Ivana and Václav, 1987 / 2006, doc), Manželské etudy – Zuzana a Stanislav (Marriage Stories – Zuzana and Stanislav, 1987 / 2005, doc), Manželské etudy – Mirka a Antonín (Marriage Stories – Mirka and Antonín, 1987 / 2005, doc), Manželské etudy – Ivana a Pavel (Marriage Stories – Ivana and Pavel, 1987 / 2005, doc)

Essay

Interwoven Temporalities

(Nicole Kandioler, film and media studies scholar DE / AT)

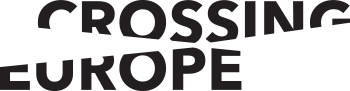

The man behind bars is in his late thirties, he has shoulder- length hair and wears a black leather jacket. At this point Helena Třeštíková and her camera team have accompanied him for about twenty years. René has spent sixteen of those years in prison. He experienced the Velvet Revolution and Václav Havel’s general amnesty. He broke into Třeštíková’s private apartment and wrote a book in prison with her support. “Was I actually ever more than an object of investigation for you?” René asks the filmmaker. After a while her voice is heard off-camera, she hesitates: “No one is only an object of investigation.”

This dialogue exemplifies the constitution of the long relationships that the Czech documentarist enters into with the protagonists of her feature-length documentary films. The absent presence of the filmmaker, her bright, ageless voice off-camera, generates a tension based on the way that Třeštíková does not have a priori control over all the questions and does not want to. The “object of investigation” asks back, and the film thus queries itself at the same time.

Her films inspired by Cinéma Vérité probe the boundaries of the documentary by raising questions about the empathy and generally about the ethics of the documentary film For her film René Helena Třeštíková was awarded the annual prize of the European Film Academy in Copenhagen in 2008, thus achieving her international breakthrough. She had already been well known to a Czech and Slovakian audience since the TV production Marr iage Stories, in which she accompanied six randomly selected, newly married couples, whom she filmed for six years. Six approximately 30-minute films were created in this first cycle, in which the young couples were at the start of their adult life. Although the life circumstances of the couples are often simple, they seem united in their fundamental confidence in the future. Following the system change, Třeštíková filmed the couples again and accompanied them into the 2000s. Marr iage Stories – 20 Years Later is not only a moving portrait of six different married couples and the ups and downs of the course of their individual lives, but also virtually a social study impressively documenting the social transition from Communism to Capitalism. At the moment Helena Třeštíková and her daughter Hana Třeštíková are working on a continuation of the Marr iage Stories with the intention of focusing on the married life of the generation of the 2000s. This is another particularity of her work: not only does her husband, the architect Michael Třeštík, share responsibility for many of the dramaturgical decisions, but also her son, the photographer Tomáš Třeštík, and her daughter, the producer Hana Třeštíková, are part of the team. For more than forty years now, Helena Třeštíková has been collecting condensed time in filmic images. The “time-collecting” method such as the long-term observation is called “časosběrná metoda” in Czech, and it aims to create a surplus of film material, which is later radically reduced through montage. The method requires patience. The passing of time that Třeštíková seeks to capture in her films also means that her own time passes. Třeštíková describes her work as a “bet on uncertainty”, thus explaining why the method is hardly wide-spread and not very popular among young Czech filmmakers.

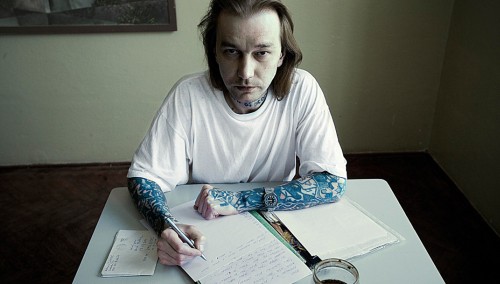

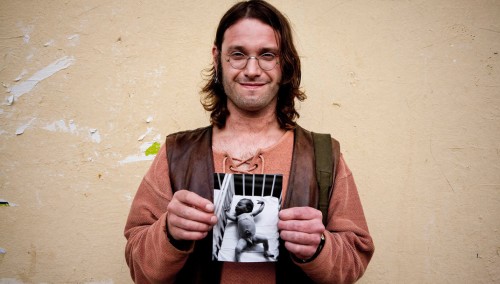

The formal diversity of the Helena Třeštíková’s film work, which consists of TV productions and cinema films, short films and feature-length films, arises from the constitution of the film material. The cinema trilogy about extraordinary ordinary people, Marcela, René, and Katka, was created in the context of several cycles produced for television. Marcela was a protagonist of the couples from Marr iage Stories, René belonged to a group of juvenile delinquents that Třeštíková interviewed in Tell Me Something About Yourself (1992). She met the young drug addict Katka for the TV cycle Women at the Turn of the Century (2000), for which she initially wanted to portray Katka’s therapist. In the manner of working described here, a kind of sociological interest in the subject is evident, which is framed in socio-political issues, such as “women and drugs”, for example, or “men in the transformation of time”. With the aim of taking a new look at Czech society after 1989, Třeštíková established the foundation “Film and Sociology” together with colleagues from film studies as well as sociologists. In the trilogy and in her more recent films, however, the focus of her work is shifted more to the individuals. The unique encounter with a person, with their ideas and wishes, the unpredictability of passing time, and the “leitmotiv” of their life are at the center of the long-term project. So from “Film and Sociology” to “Human and Time”, the name of the association Helena Třeštíková founded in 1994 with her husband, the program of which is to reflect on “the human being and the changes that come with the passing of time”. In Vojta Lavicka – Ups and Downs she accompanies the Czech Roma musician and activist of the same name, whose life is devoted to the struggle against anti-Roma resentment in Czech society. Jakub Špalek – Life with Jester documents the life of the theater director and actor, who entered into history as one of the leading student voices of the Velvet Revolution. Mallory shows the impressive fate of a woman, who not only finds a way out of drug addiction, but also gives her life a positive turn under the most improbable conditions and starts training as a social worker at the age of over fifty.

The heroines and heroes of Helena Třeštíková’s are, on the one hand, unknowns who do not necessarily appear interesting at first glance. On the other hand, they are contemporary public figures, who have written Czech history in one form or another. What they all have in common is that they allow the filmmaker a glimpse into their private lives and that they are willing to reflect on their role in society and on their fate: from the prisoner René Plášil to the author and president Václav Havel, from the drug addict Mallory Neradová to the controversial UFA star Lída Baarová.

In her most recent film Lída Baarová – Doomed Beauty Helena Třeštíková interweaves shots for her television film Lida Baarova’s Bittersweet Memories (1995) with film material from the Czech film archive NFA, from the National Film Archive Washington, and from private collections together with Baarová’s autobiographical memories.

The astonishing result of that montage looks like this: From off-camera we hear the frail voice of an old woman. We see Lída Baarová loaded with boxes running through the summery big city of Prague in black and white: she is a young woman – as an actress not yet quite at the zenith of her career. Her bright, modern dress contrasts her dark hair and eyes. Cars, trams, bicycles, and coaches rush through the picture, men and women hurry across the intersection. At the side of the street Baarová sets her boxes down for a moment and sits on a bench, where she watches two swans in the water. She takes a piece of paper out of her bag and seems to write down what the old woman is dictating to her from off camera. “When one becomes older, one likes to take stock. How was my life? Did it have any meaning? Would I do something different, if I could live again? Thoughts like these are probably not alien to anyone. For me they are proof that we human beings are indeed more than living little machines, and that a voice speaks to us from an unknown place, which is the voice of our conscience. And when I think about this principle, I hear this voice not as the voice of a judge, but as that of a benevolent and understanding friend. Some will say: Naturally! After all that she experienced, she needs a friend more than a judge. Perhaps.”

In the sensitively arranged shot, Helena Třeštíková and her co-director Jakub Hejna create a montage with a scene from the legendary film The Seamstress (1936) by Martin Frič and a passage read by Alena Šislerová from Baarová’s autobiography. In a reflexive gesture, what we hear (Baarová’s self-critical remarks about her life) is commented on by what we see (a scene from a film about a young, ambitious seamstress, who wants to become a great fashion designer). And what we see seems to become suddenly detached from the narrative context, archived forever in a radical presence. The wonder of film is evident in this moment, which seems to be more capable than any other medium of depicting the antagonistic moments of a life, its potential and its contradictoriness in one shot: the promising young star at the beginning of World War Two against the backdrop of a democratic, economically rising Prague, and a rueful old woman, who has been forgotten. Doomed Beauty differs from Třeštíková’s other films to the extent that the archive material constitutes the time frame of the long-term observation and not the conversations otherwise conducted over the course of long years. Yet an analogy to the method of querying people in her long-term documentaries suggests itself in the unprejudiced way that Třeštíková queries the archive material, detaches it from its context and reanimates it. Accessing the archive material seems to cite what Svetlana Boym suggested in The Future of Nostalgia with the Russian figure of speech: “The past has become even more unforeseeable than the future.” Grasping the past as unfinished and the life of a single person with the greatest openness possible, whether they are unknowns or historical personalities, that is the promise that lies in Helena Třeštíková’s documentary gesture.

Třeštíková developed her longest long-term study to date from a film about the birth of the first child of her friend Jana (The Miracle, 1975). Thirty-seven years from the life of the Kettner family and especially of the firstborn son, Honza, are documented in Private Universe.

Here too, Třeštíková works on the one hand with archive material from television, on the other with a different medium of long-term documentation, the diary. In the juxtaposition of the film shots and the literary documentation of family life (by the father Petr), the specific feature of the “time collecting” method is evident: it is the “here and now” that interests Třeštíková, “life as it is”, which Dziga Vertov already wanted to capture with the camera. She returns in periodic diachronic loops to a respectively current “here and now”, but one that can always only be grasped retrospectively. Like the diary, the long-term documentary film also reveals a reflection on what has already happened. Like the diary, the long-term documentary film also has gaps. It is in these gaps that time passes. Keeping the different temporalities in view, arranging a continuous and binding contact with the protagonists is one of the greatest challenges of a long-term project. In a conversation with the Czech actor Jan Krause about her work, Třeštíková recently referred laconically to the socialist heroine of her childhood, a weaver who worked at twenty-six looms at the same time. Třeštíková considers her work in analogy to this anecdote as an interweaving of different temporalities in different places. The focus here is less on experimenting with the form, but rather on the material of life itself, which imports an experimental aspect into the film work to the extent that it is wholly unforeseeable.

In the epilogue of Private Universe we see Jana again, the mother of the Kettner family. The two daughters are married, and the rebellious son seems to be gradually growing up. Energetically she calls into the camera: “And tomorrow we can die, Helena. We’ve taken care of everything.” (...) She runs her hands through her hair, looks into the camera and laughs: “Why are you shaking your head? Why are you smiling so slightly?” From off-camera: “Well, that we can die tomorrow. I hadn’t thought about that at all.” Jana: “I think about it constantly.” Cut. A still appears on the screen of the filmmaker and Jana Kettner holding a photograph up to the camera, in which they are both depicted as little girls. Fade to black. The end.

As in the scene in René described in the beginning, here too the direction of questioning is reversed again, and with the description of her smiling and shaking her head, the filmmaker appears in the imagination of the audience. The film comments here in a complex way on the friendship between the two women and the relationship of past, present and future. In Jana’s reference to death, though, there is also a question about the end of a long-term documentary film. There is no answer to this question. Even though the life of an individual is finite, the end of a long-term documentation is by definition provisional.