Essay

Excavation Work

(Bert Rebhandl, film critic DE/AT)A little boy and a girl are playing in a meadow in a park. The light is bright and friendly, the pictures are in black and white, the shadows lie gently on the ground, birds chirp in the trees. Everything indicates an ideal summer day in Riga, nothing should overshadow the good mood. And yet there is something about this recreational landscape that cannot be denied and which gradually becomes apparent in Sergei Loznitsa’s thirty-minute documentary film The Old Jewish Cemetery. The park is simultaneously a Jewish cemetery, where the communities of Riga have buried their dead since 1725. Following the invasion of the Germans in World War Two, the cemetery became a mass grave; under the Communist regime the tombstones were used as building material, and after 1989 this area became an urban recreational area, which Sergei Loznitsa shows in his film. At a closer look, there are still traces of former destruction to be found, and so we are dealing with an example of the historical landscapes that are never “innocent”, which occupies Loznitsa in his work. Because of his birth in Belarus, his young years in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, his film studies in Moscow, and later documentary works in St. Petersburg (before moving to Berlin in 2000), he is also personally familiar with these three successor states to the Soviet Union. Yet he also includes the Baltic in his works, and if we are looking for a common denominator, Timothy Snyder’s term “Bloodlands” suggests itself, the parts of Eastern Europe that suffered especially intensively in the twentieth century under fascist as well as socialist crimes.

With his most recent film In the Fog, he turns Belarus into a “Bloodland” in any case (based on stories by Vasil Bykaŭ, one of the most important authors from this country), in which the simple people try to survive as they are almost hopelessly trapped between the fronts. The Nazi occupiers, the partisans, a man who works for the railway – Loznitsa takes them all into view, thus finding access to a history “from below”, which does not leave out the fate of the ordinary people.

If the conceptual documentary film The Old Jewish Cemetery and the feature film In the Fog have something in common, then one would have to speak first of the unusual photography. Loznitsa is an aesthete par excellence, searching for an image language with a depth of focus, which combines elements of the panorama with allegorical strategies, in which the concrete image refers to larger contexts. In the Fog begins with a masterly long take of the execution of several partisans, which is reminiscent of Tarkovsky in the density of its details and the linking of various commonplace and metaphysical aspects, but then switches into a three-person drama in open nature and ends on a tragic-absurd note.

Due to the events in the Ukraine, it was demonstrated to Europe again in 2014 that the history of World War Two is by no means over, but still continues to serve as a background for the interpretation of current events. To this extent, the film fits very well into Loznitsa’s overall work, as he worked for a long time in the documentary field and presented his first feature film, My Joy in 2010. In this story about a truck driver in the Russian province, the War already comes up as an old man recalls his return in 1946, a sobering experience that has nothing at all to do with the official heroic mythology of the great patriotic war. In My Joy, Loznitsa sketches a depressing image of life in the back country of a historical former major power. As in In the Fog, here too the sublime and indifferent nature filmed by the Romanian cameraman Oleg Mutu forms a striking opposite to the need and the violence among human beings. It also forms the background for a series of documentary films, in which Loznitsa shows people in exposed areas and how they cope with life: Life, Autumn about a village near Smolensk, Artel about fishermen on the White Sea, Northern Light about a commune in Karelia. The two films about psychiatric institutions in Russia (Settlement and The Letter) can also be seen in this context, and in Portrait the consistent photographic interest is imbued with a reflective facet, as the transitions between still photography and moving image are purposely blurred. The specific “conditio humana” that Loznitsa seeks to bring into view with a multitude of artistic strategies has a crucial precondition in the experience of really existing Socialism. The early films often deal with this in one way or another. The debut film Today We Are Going to Build a House can already be seen as an allegory for the greater Socialism: images of the construction of a residential building by a group called Tekton, collectively working on a project that is to serve all. These are images that were originally supposed to serve a propagandist intention, but appear as liberated from the ideological context with Loznitsa. With his incisive dubbing and the soundtrack of Baltic ballads and polkas, he makes Socialism come paradoxically to life, no longer as an encumbrance of two or three generations, which will therefore never arrive in the present, but rather as a possibility of perhaps being able to deal with this legacy differently from what is prescribed by allencompassing capitalism and the neo-imperial politics of Russia under Putin.

Loznitsa has worked several times with archive material from the Soviet Union. In Revue the hopes are most clearly recognizable that were once directed to the project of building up a Communist structure: propaganda material from the era of de-Stalinization, including many theater recordings, shows how a society on the progress vector seems to stretch itself forward, trying to outdo itself and yet not lose its soul at the same time. The soul, that is the pathos that seems to inhere to Russian culture, the feeling that is recognizable in dances and songs, in which the hard work at the blast furnaces is balanced out. Revue makes the Soviet Union’s endeavors to catch up in the competition of systems appear playful, and this is specifically what results in the painful irony of this film, because this was naturally an illusion, first of all, and secondly the whole effort was in vain, at least if it is considered under the aspiration to create a better society.

With Blockade Loznitsa returned to an earlier key scene in the battle of the systems. He edits in material from the time when Leningrad was besieged by the German army. We see images of a city defending itself, in the end there are fireworks. For the devastating starvation during the blockade there are hardly any images, with the exception of a longer sequence showing how corpses are disposed of – they are taken to the collection point on sleds; finally we look right into the face of a dead person. Leningrad is a mass grave, and yet the city survived.

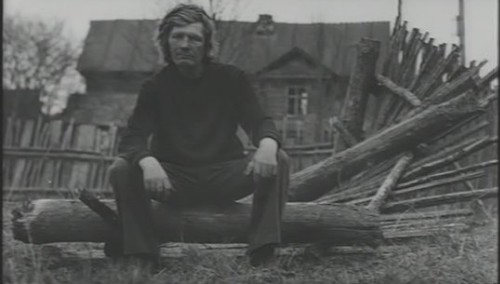

The people who can be seen in these last images of Blockade are at least apparently related to the people in the film Landscape, which Loznitsa shot at bus stops in Russia. The camera pans continuously to the right, carries out circular movements, in which it captures quite a bit, as though by accident: faces, buildings, streets. Most of all, there are faces, many of them barely recognizable under hats pulled low against the “winter, this son of a bitch”. As in all of Loznitsa’s films, the soundtrack has an elementary significance here.

What we hear are scraps of conversations from these situations of waiting; we are given insights into family situations, a man explaining to his wife that he no longer wants to be nice to her, but instead wants to show her who the man in the house is. Allusions to political processes and corruption encounter general resignation, the young men have red cheeks from beer and the cold. This is the image of a Russia we think we know, stuck deep in situations that seem not to have changed for decades or even longer. The limping figure leaving the picture in the last scene could be from the nineteenth century without the bicycle, a serf plodding tediously through life.

The danger of aestheticizing misery is banished here through the relation of image and sound: the image is distant and has an artistic touch, but the soundtrack turns Loznitsa into someone who listens to the “whisperers” (the title of a famous book by Orlando Figes about private life under Stalin) and bears witness to their complaints that are barely ever mentioned aloud.

In general, there is something fragile about Loznitsa’s documentary works, which reveal their vulnerability. One of his most recent works, The Letter, in which he deals with psychiatric patients again, recalls in its photographic quality films by Alexander Sokurov, who could be called the painter among Russian filmmakers. Loznitsa frequently alternates between detailed precision in the depth of focus and blurred surreality, thus conveying the impression that there could be two documentary realisms: one from the outside, corresponding to the conventional view of people and things, and one with which the film artist attempts to aesthetically enter into the observed. This procedure is especially evident in The Train Stop, in which people are seen, who have fallen asleep waiting at train stations. We see them from the outside, yet we are strangely drawn into the unconsciousness of their posture. The approximateness of the images and the train station sounds from offscreen result, as a whole, in a strong metaphor for a world of transition, as it was undoubtedly subjectively felt to be in St. Petersburg in 2000.

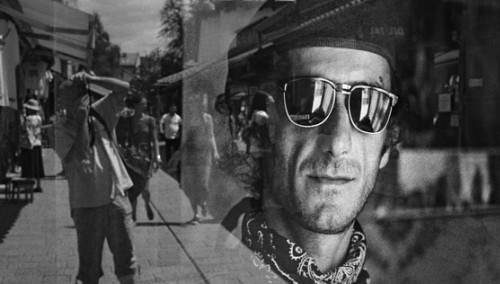

In 2013 Loznitsa began filming protests against the Yanukovych regime in the Maidan in Kiev. The result was a distanced documentary film about a popular revolt, which interested Loznitsa initially due to the diversity of the rallies and the logistics. He shows how during the weeks of protest many simple people took the stage and argued in their own words for the changes demanded in the Maidan. A state theory from below becomes recognizable here, while the call is repeatedly heard in between, “get rid of the pack”, and finally the whole film sinks into the dark clouds of battles around Maidan, Kreshtshtyak and Institutskaya Street. Many proponents of the Ukrainian revolts found Maidan distanced, but Loznitsa insisted here too on his own, artistic truth and indeed captured much of the dramatic mood of those days without relying on any gestures of authenticity, reportage television, or smartphone documentarism. The reason why the film is outstanding is because it actually takes a historical position even in the moment of conflict: it shows Maidan as a site of “nationbuilding”, and this is exactly why the Ukrainian experience was so offensive to the regime of the great neighbor Russia.

There are many retarding moments to be found in Loznitsa’s films; his work is marked by an ambivalence toward “second-hand time” (Swetlana Alexievich), which marks the experiences of many post-Soviet people – a time that was really already used up, but still had to be carried on, because the new time did not fit. It is only recently that Loznitsa has occasionally taken up projects that have nothing to do with his Eastern European origins. That has to do with his growing success in the international festival landscape, which brings him into contact with all kinds of projects. Most recently, a German film subsidy approved funding for a project with the title Austerlitz, where there is talk of a meditation on a concentration camp and the culture of remembrance. Loznitsa has already contributed several crucial works to this culture and proven that the medium of film is excellently suited to represent historical complexity.